Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

Yellow is aug 5

Former Philippine President Corazon C. Aquino was interred on August 5, 2009 at the Manila Memorial Park in Parañaque City. The funeral cortege from the Manila Cathedral in Intramuros lasted for 8 hours as thousands upon thousands of supporters, most of whom wore Aquino’s signature yellow color, flooded the route. In 1986 she led a peaceful people’s uprising that deposed then-President Ferdinand E. Marcos and installed her as the country’s new leader. Tita Cory, as she was fondly called, was diagnosed with colon cancer early in 2009 and finally succumbed on August 1. She was 76.

Bakwits

Evacuees loiter in the shade inside a warehouse in Pikit, North Cotabato. People numbering in the hundreds of thousands (half a million, by one estimate) were displaced from their homes in Central Mindanao by armed clashes between the Armed Forces of the Philippines and Moro Islamic Liberation Front forces last August. Locally called "bakwits" (from "evacuate," it is a colloquial term for evacuees), they were forced to endure inhospitable conditions in makeshift evacuation centers, where they faced hunger, unsanitary environs, an unforgiving weather, and uncertainty.

A couple of evacuees in a warehouse in Pikit, North Cotabato try to sleep off the nightmare that is their sudden flight.

Ashes are what remains of a house in Midsayap, North Cotabato after a skirmish between government troops and rebel forces. People numbering in the hundreds of thousands (half a million, by one estimate) were displaced from their homes in Central Mindanao by armed clashes between the Armed Forces of the Philippines and Moro Islamic Liberation Front forces last August.

Makeshift tents are set up in the muddy surroundings of a warehouse in Pikit, North Cotabato for evacuees to take refuge in.

Evacuees fill every inch of the concrete bleachers of the parish gymnasium in Pikit, North Cotabato.

An evacuee tries to get by with almost nothing in a trading center-turned-evacuation center in Aleosan, North Cotabato.

An enterprising evacuee transfers his entire sari-sari store to a warehouse in Pikit, North Cotabato, to where he and his neighbors fled.

An evacuee with her laundry navigates a maze of densely packed tents in a park-turned-evacuation center in Datu Piang, Maguindanao.

Evacuees gather around a water pump to do their laundry at the back of a public school-turned-evacuation center in Datu Piang, Maguindanao.

Evacuees in Mamasapano, Maguindanao converge beside a truck loaded with sacks of rice. They wait for their turn to claim sacks of rice being distributed by a non-government organization.

Evacuees clutching claim stubs form a queue as a non-government organization prepares to distribute sacks of rice in Mamasapano, Maguindanao. Community and Family Services International (CFSI) personnel get ready to distribute sacks of rice from the World Food Programme to internally displaced people in Mamasapano, Maguindanao.

A volunteer worker of the Department of Health in Mamasapano, Maguindanao takes a short break from the overwhelming task of assisting ailing evacuees.

Anti-aerial spray caravan

Participants get ready for the Batok sa Makahilong Ulan Davao City-Bukidnon-Cagayan de Oro City Caravan. Mamamayan Ayaw sa Aerial Spray (MAAS) organized the event as part of their 2-month long Lihok sa Katawhan Batok sa Makahilong Ulan Campaign to pressure the Court of Appeals to uphold Davao City's ordinance against the banana plantations' aerial spraying (from low-flying aircraft) of pesticides. Just this January 12 the court made public its decision: the plantations may proceed with its practice of aerial pesticide spraying. There are documented cases of people getting sick, and in a few instances even dying, from exposure to such aerial spraying.

A jeepney is raring to go and join the caravan against the aerial spraying of pesticides in Davao banana plantations.

The caravan against the aerial spraying of pesticides in Davao's banana plantations navigates in the dark as it proceeds toward Cagayan de Oro City.

Caravan participants get off the jeepneys to stretch their limbs after a couple of hours of traversing the highway between Davao City and Cagayan de Oro City.

Caravan participants get some shuteye inside their jeepneys. From Davao City they set off for Cagayan de Oro City at midnight, a trip that eventually took them 12 hours.

Participants in the Batok sa Makahilong Ulan Davao City-Bukidnon-Cagayan de Oro City Caravan last March 12 take turns speaking out against aerial praying during one of their city stops.

Caravan participants enjoy the cool air of Malaybalay City during a stop on their way to Cagayan de Oro.

A concerned resident of Davao City speaks out against the dangers of pesticide aerial spraying.

Finally in Cagayan de Oro City, the caravan participants proceed on foot toward the Court of Appeals where Davao City's ordinance against aerial spraying was being deliberated on.

A judge of the Court of Appeals mingles with the crowd to hear what they have to say. She eventually grants them an audience in her sala.

Two judges of the Court of Appeals dialogue with the caravan participants, assuring them of the court's impartiality in dealing with any and all issues.

Having their voice heard by the judges, the Batok sa Makahilong Ulan Davao City-Bukidnon-Cagayan de Oro City Caravan last March 12 gets ready to roll out for home.

Lumad ritual

Tribal leaders, or "datus," walk toward a pre-determined spot where they wil perform a ritual sacrifice or "pamaas." The indigenous peoples or "lumad" of the Philippines consider such rituals are an essential part of their culture. They usually sacrifice chickens and pigs as offerings to spirits.

A panicky pig is restrained to prepare it for a ritual sacrifice or "pamaas."

A tribal leader, or "datu," stabs a pig with his bolo as part of a ritual sacrifice or "pamaas."

A tribal leader, or "datu," performs a sacrificial ritual called "pamaas." Here a chicken is being offered in thanksgiving to the spirits.

On a house's floor are seen evidence of a tribal leader, or "datu," having performed a sacrificial ritual called "pamaas." Here a chicken is being offered in thanksgiving to the spirits.

Maitum anthropomorphic jar finds

The road to the cave in Maitum, Saranggani where fragments of anthropomorphic jars were found is rocky and dusty, but the scenery is picturesque.

The small mouth of the cave where fragments of anthropomorphic jars were discovered is barricaded with debris to frustrate any attempt at theft.

One of the local residents who discovered the potsherds pose outside the cave's portal. Quarrying activities for limestone on a hillside in Maitum, Saranggani yielded anthropomorphic pottery fragments. An investigation by the Philippine National Museum prompted them to declare the site a prehistoric burial ground, similar to a landmark discovery 17 years ago in the same area. A constant risk, however, is looting as local residents suspect that treasure is being excavated as well.

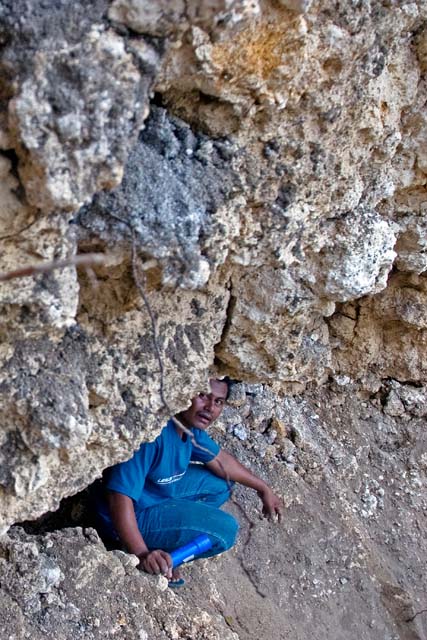

The curious have to crawl on all fours if they want to see ancient potsherds. Quarrying activities for limestone on a hillside in Maitum, Saranggani yielded anthropomorphic pottery fragments.

The shadowy profile of a man stands guard outside the opening of an ancient burial ground where anthropomorphic pottery fragments have been found.

Onlookers can't get enough of the ancient potsherds discovered in their neighborhood. An investigation by the Philippine National Museum prompted them to declare the site a prehistoric burial ground, similar to a landmark discovery 17 years ago in the same area. A constant risk, however, is looting as local residents suspect that treasure is being excavated as well.

A local resident holds up an anthropomorphic jar fragment for curious onlookers to see.

A crowd gathers outside the mouth of a cave where fragments of anthropomorphic jars were accidentally discovered by a quarrying team.